Basic Microbiology Laboratory Practices

Microbiology labs adhere to rules ensuring safety and accurate results․ Practices involve sterile techniques to prevent contamination․ Labs require organized workflows for efficiency․ Proper waste disposal is crucial to avoid environmental hazards․ These fundamentals underpin successful microbiology experiments․ Manuals explain techniques for teachers and technicians․

Techniques for Culturing Microorganisms

Culturing microorganisms is a cornerstone of microbiology, involving the growth of microbial populations in a controlled environment․ Various techniques exist, each tailored to specific research questions and microbial needs․ Understanding these methods is vital for anyone working in a microbiology lab, as they form the basis for many downstream applications․

One of the most common techniques is streak plating, used to isolate pure cultures from a mixed population․ This involves spreading a sample thinly across an agar plate, allowing for single colonies to develop from individual cells․ Spread plating, another method, involves diluting a sample and spreading it evenly over the agar surface for uniform growth․ Pour plating mixes the sample with molten agar, which is then poured into a petri dish to solidify, resulting in colonies growing both on and within the agar․

Liquid cultures, grown in broths, are used for large-scale microbial growth or when quantifying growth rates․ These cultures may be aerated or maintained under anaerobic conditions, depending on the microorganism’s requirements․ Specialized media, such as selective or differential media, are used to isolate specific types of microorganisms or to distinguish between different species based on their metabolic capabilities․ Mastering these techniques is crucial for advancing knowledge in microbiology․

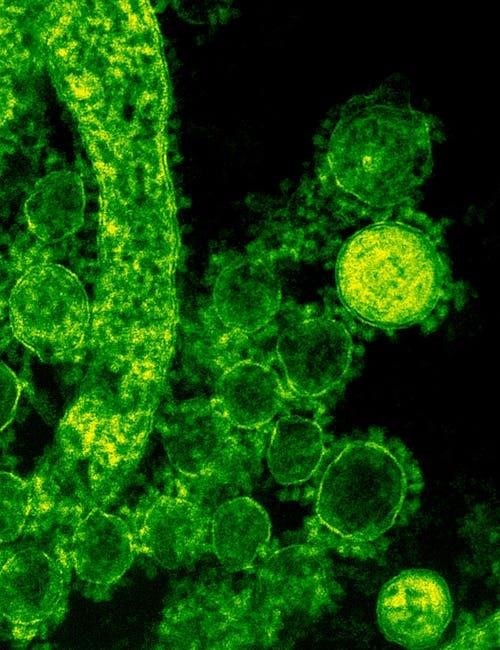

Methods for Identifying Microorganisms

Identifying microorganisms is a crucial aspect of microbiology, relying on diverse techniques that examine morphological, biochemical, and genetic characteristics․ Traditional methods involve microscopic examination, observing cell shape, size, and staining properties like Gram staining, which differentiates bacteria based on cell wall structure․ Biochemical tests assess metabolic capabilities, such as enzyme production and substrate utilization, providing a “fingerprint” for each species․

Modern approaches include molecular techniques, offering rapid and accurate identification․ Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) amplifies specific DNA sequences, allowing for species-level identification through DNA sequencing or analysis of restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLPs)․ 16S rRNA gene sequencing is widely used for bacterial identification, comparing the highly conserved gene sequence to databases of known species․

Mass spectrometry, particularly MALDI-TOF MS, has revolutionized microbial identification by analyzing the unique protein profiles of microorganisms․ This technique provides rapid and cost-effective identification, making it a valuable tool in clinical and research settings․ Proper identification is crucial for understanding microbial roles in various ecosystems and for developing effective strategies for disease control and prevention․ These methods combined provide a comprehensive approach․

Procedures for Analyzing Various Samples

Analyzing diverse samples in microbiology involves tailored procedures to isolate and identify microorganisms․ Environmental samples, like soil and water, require serial dilutions and plating to quantify microbial populations․ Clinical specimens, such as blood or swabs, undergo specific treatments to enhance pathogen detection, often involving selective media to inhibit non-target organisms․ Food samples necessitate homogenization and enrichment steps to detect spoilage organisms or pathogens․

Each sample type demands appropriate controls and standardized protocols to ensure reliable results․ Quality control measures, including the use of known positive and negative controls, are essential for validating the accuracy of the analysis․ Data interpretation involves comparing results to established reference ranges and considering the limitations of each method․ Proper documentation of procedures and results is crucial for reproducibility and traceability․

Advanced techniques like flow cytometry and microscopy are applied for detailed analysis of cell populations and structures within the samples․ The goal is to accurately characterize the microbial composition and assess its impact on health, environment, or food safety․ Effective analysis relies on rigorous adherence to protocols and a thorough understanding of microbial ecology․ Effective analysis relies on rigorous adherence to protocols․

Aseptic Technique in Microbiology

Aseptic technique is paramount in microbiology to prevent contamination of cultures and maintain purity․ This involves sterilizing equipment using autoclaves or other methods to eliminate unwanted microorganisms․ Work surfaces are disinfected regularly to create a sterile environment․ When transferring cultures, techniques like flaming loops and tube mouths minimize contamination risks․ Personal protective equipment, such as gloves and lab coats, further reduces the chance of introducing contaminants․

Proper hand hygiene, including thorough washing with antiseptic soap, is critical before and after handling cultures․ Opening Petri dishes or tubes should be done carefully and quickly to limit exposure to airborne particles․ All materials coming into contact with cultures must be sterile to avoid introducing foreign organisms․ Regular monitoring and validation of aseptic practices are essential to ensure their effectiveness․

Training in aseptic technique is a fundamental aspect of microbiology education․ Mastering these skills ensures reliable experimental results and prevents the spread of potentially harmful microorganisms․ Furthermore, aseptic techniques are indispensable for maintaining sterile conditions when working with microbial cultures․ Aseptic techniques are indispensable for maintaining sterile conditions․ The goal is to isolate pure cultures․

Culture Techniques in Microbiology

Culture techniques are essential for growing and studying microorganisms in the laboratory․ Different methods exist, each suited to specific organisms and research goals․ Streak plating is a common technique for isolating pure cultures by diluting bacterial cells across an agar surface․ Spread plating involves evenly distributing a diluted sample onto an agar plate to obtain countable colonies․

Pour plating mixes the sample with molten agar before pouring it into a Petri dish, allowing colonies to grow within the agar and on the surface․ Broth cultures are used for growing large quantities of microorganisms in liquid media․ Specific media formulations are designed to support the growth of particular organisms or to differentiate between them․

Environmental factors like temperature, pH, and oxygen levels are carefully controlled to optimize microbial growth․ Incubation conditions vary depending on the organism’s requirements․ Anaerobic organisms require oxygen-free environments․ Specialized equipment, such as incubators and anaerobic chambers, are used to maintain these conditions․ Proper technique and sterile procedures are vital․ Culture purity is essential for reliable results․ Careful observation of the growth characteristics aids identification;

Bacterial Identification Methods

Identifying bacteria is crucial in microbiology for diagnostics, research, and environmental monitoring․ Various methods exist, each with its own principles and applications․ Microscopic examination is a primary step․ It reveals cell shape, size, and arrangement․ Gram staining differentiates bacteria․ It classifies them as Gram-positive or Gram-negative based on cell wall structure․ Biochemical tests assess metabolic capabilities․ These tests include enzyme production and substrate utilization;

Selective and differential media aid identification․ They promote the growth of specific bacteria․ They also differentiate based on metabolic characteristics․ Serological tests use antibodies․ These tests detect specific bacterial antigens․ Molecular methods identify bacteria․ These methods use their genetic material․ PCR amplifies specific DNA sequences․ Sequencing determines the exact genetic code․

Mass spectrometry identifies bacteria based on protein profiles․ Automated systems streamline identification․ They combine multiple tests for efficiency․ Interpretation of results requires expertise․ Careful comparison to known characteristics is essential․ Accurate identification relies on a combination of methods․ Confirmation with multiple tests is crucial․ These methods provide valuable insights into bacterial diversity․ They also provide insights into their roles in various environments․

Effects of Growth Factors on Microbes

Microbial growth is significantly influenced by various growth factors․ These factors encompass physical and chemical conditions․ Temperature plays a crucial role․ Different microbes thrive at specific temperature ranges․ pH affects enzyme activity․ It, therefore, affects nutrient transport․ Osmotic pressure impacts cell integrity․ It determines water availability․

Nutrients are essential for growth․ Carbon sources provide energy and building blocks․ Nitrogen is needed for protein synthesis․ Phosphorus is vital for nucleic acids․ Sulfur is part of some amino acids․ Trace elements are required in small amounts․ They act as enzyme cofactors․ Oxygen availability influences growth․ Aerobes require oxygen․ Anaerobes cannot tolerate it․ Facultative anaerobes can grow with or without oxygen․

Specific growth factors enhance growth․ Vitamins act as coenzymes․ Amino acids provide building blocks․ Purines and pyrimidines are needed for nucleic acids․ Growth factors vary among microbes․ Some can synthesize their own․ Others require them from the environment․ Understanding these effects is crucial․ It helps in controlling microbial growth․ It also helps in culturing microbes in the lab․ Studying these factors helps us understand microbial ecology․ It also helps us understand microbial pathogenesis․